|

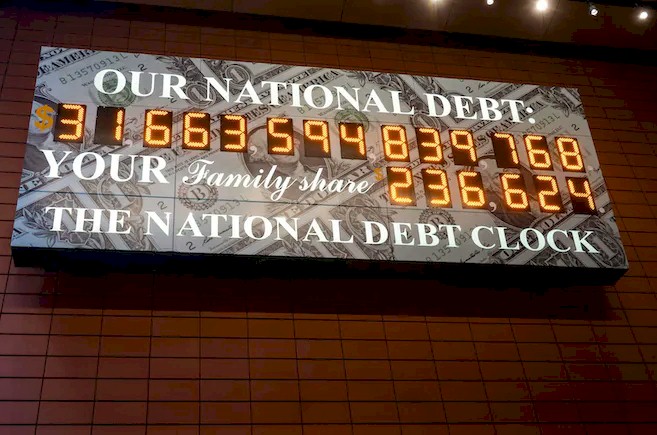

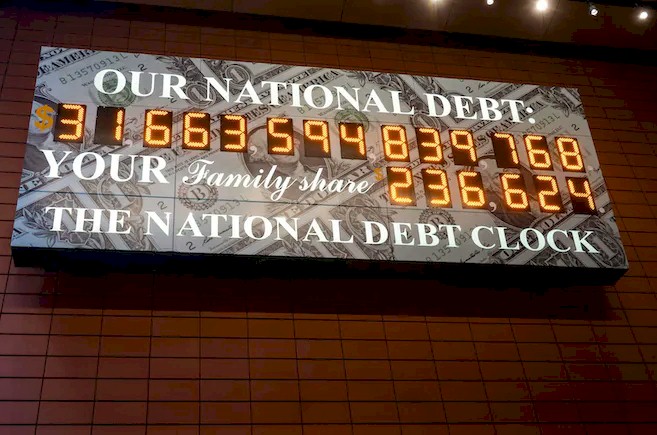

How the return to Federalism

can control the

debt and lower the cost of the

Federal government.

In accordance with the U.S. By virtue of the

Constitution, the federal government was endowed with limited and specific

authority, while the majority of governmental responsibilities were

delegated to the states. In order to underscore the constraints on federal

authority, the Founding Fathers of the United States of America ratified the

Tenth Amendment, which states, "The powers not delegated to the United

States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved

to the States, respectively, or to the people." This amendment exemplifies

federalism, which James Madison defined in Federalist No. 45 as the belief

that federal and state governments have distinct policy domains and that

federal activities are "limited and defined."

Local and state fiscal affairs were largely out of the purview of the

federal government until the middle of the 20th century. Subsequently,

however, Congress has intervened more frequently through "grant in aid"

programs, which consist of state subsidies accompanied by top down

regulations. Presently, the federal government offers over 1,300 assistance

programs for housing, transportation, highways, health care, and numerous

other endeavors.

In 2019, federal assistance to the states was $721 billion in total. Then,

in an effort to combat the pandemic, Congress substantially increased aid to

an estimated $1.23 trillion in 2022, $829 billion in 2020, and $1.25

trillion in 2021. The years in question are fiscal in nature. Local and

state tax revenues have increased substantially over the past two years,

providing governments with the means to manage the crisis. As a result, the

majority of this aid was ultimately unnecessary.

The states have developed an excessive reliance on federal assistance. The

federal government does not have regional subdivisions in the form of state

administrations. Creating a costly bureaucracy, diminishing political

accountability, stifling diversity, and undermining local democratic control

are all outcomes of the aid system. The subsequent discourse examines nine

justifications for the reduction of federal aid.

There are nine justifications for reducing federal aid.

1. Assistance encourages extravagant expenditures. Advocates of federal aid

frequently assert that state governments are financially incapable of

financing programs, while the federal government appears to possess

boundless financial resources. Large deficits provide the appearance of

substantial coffers on the part of the federal government; however, each

dollar of federal aid for state programs ultimately originates from state

taxpayers. Because state governments are more fiscally prudent than the

federal government and must balance their budgets and limit debt issuance,

it is preferable to fund state activities at the state level.

State policymakers weigh the benefits of spending against the costs of

increasing taxes to finance programs that are funded internally.

Nevertheless, in the case where federal aid contributes to the funding of a

program, state and federal policymakers share in the credit for the

expenditures while bearing only a portion of the tax liability. Federal aid

induces excessive spending by inflating the proportion of political benefits

derived from expenditures relative to the associated tax costs.

Additionally, numerous federal aid programs necessitate that states

contribute a portion of the funding, thereby encouraging further

expenditures. In the case of Medicaid, where the federal reimbursement is

open-ended, states are motivated to consistently expand their programs in

order to receive additional funding from the federal government. By

converting matching programs to fixed block grants, squandering incentives

could be reduced.

2. Aid influences purchasing decisions. Advocates of aid anticipate that

federal authorities will effectively distribute funds to endeavors of

significant value throughout the country. However, there is no evidence to

suggest that federal authorities possess a superior ability to allocate

resources for housing, transportation, education, and other endeavors than

state authorities. In fact, flawed formulas and pork barrel politics

frequently impede the efficient allocation of federal aid.

Certain developing states, including Texas, receive inadequate assistance in

comparison to the petroleum tax revenue they contribute to the federal

transportation fund. Federal assistance for airports is disproportionately

allocated to smaller airports, neglecting larger airports that would yield

greater benefits. Similar to this, rural areas with low terrorism threats

have received a disproportionate amount of assistance for homeland security.

Although the common perception is that federal aid is intended for less

developed areas, this is rarely the case. The ten states with the highest

per capita income in 2019 received $2,354 in federal aid, while the ten

states with the lowest per capita income received $2,068, according to my

calculations. The fact that Medicaid's matching formula has incentives more

affluent states to expand the program than impoverished states has

contributed to this circumstance; as a result, wealthier states receive more

matching dollars from Washington.

States are incentivized by federal aid to allocate greater resources towards

activities that are subsidized by the federal government while allocating

fewer funds towards other activities that may be preferred by state

residents. As an illustration, the allocation of federal transit aid

primarily towards capital expenditures rather than operational costs has

prompted dozens of municipalities to invest in costly rail systems as

opposed to more fuel-efficient bus systems.

The states have been compelled to make expenditure decisions unrelated to

the requirements of their own citizens as a result of federal aid. The urban

renewal or "slum clearing" initiative of the middle of the 20th century,

which utilized billions of dollars in federal aid to demolish impoverished

neighborhoods in favor of unsuccessful redevelopment plans, is a classic

example. Jane Jacobs stated in The Death and Life of Great American Cities

regarding these initiatives, "This is not the reconstruction of cities. This

constitutes the city-sacking."

3. Aid is the cause of bureaucracy. For aid programs to prepare

applications, devise procedures, file reports, submit waivers, audit

recipients, litigate disputes, and comply with regulations, legions of

administrators, accountants, and attorneys are required. The application

process for federal aid is laborious and can require hundreds or even

thousands of pages to comply with the numerous federal regulations. Selected

states were awarded $4.3 billion in Race to the Top school grants during the

Obama administration. However, in order to qualify, states were obligated to

submit applications that typically exceeded 600 pages in length.

In conjunction with state and local administrative expenses, the federal

administrative costs of aid programs may devour as much as 10 percent of

program expenditure. For instance, local governments spent an average of 17

percent of Community Development Block Grant funds on administration,

according to the Government Accountability Office (GAO). Millions of state

and local government employees are necessary to manage federal aid spending

and related regulations, according to Paul Light's research on the "true

size of government."

4. Aid fosters abuse and fraud. Fraud, abuse, and excessive waste are

problems in numerous federal aid programs. The provision of "free" funds

from Washington provides state administrators with little motivation to

curtail such expenditures. Congress members, on the other hand, are

politically motivated to support all federal expenditures in their

districts, which provides little incentive to reduce such waste.

Consider Medicaid, the largest assistance program. 21 percent, or $85

billion, of the program's expenditures in 2020 were improper, erroneous, or

fraudulent, according to the GAO. State administrators are less motivated to

reduce Medicaid waste as a matching program requires them to identify waste

exceeding two dollars in order to save one dollar for state taxpayers. In

fact, the states engage in questionable strategies to inflate the matching

dollars they receive from Washington in order to abuse Medicaid.

The school breakfast and lunch programs receive substantial federal funding

that is also susceptible to pervasive misuse. In 2019, the GAO reported that

school breakfasts and lunches were improperly compensated at a rate of 23%

and 23%, respectively. Local administrators perform minimal recipient

eligibility verification due to a lack of motivation to do so.

Administrators are, in fact, motivated to exaggerate the number of children

who are eligible for benefits.

As a result of the lack of incentives to exercise cost control,

infrastructure projects that receive federal funding frequently experience

budget overruns. The cost of the Big Dig highway project in Boston increased

by more than fourfold, from $2.6 billion to $14.6 billion, with the federal

government contributing $8.5 billion of that amount. Randal O'Toole found in

his 2018 book Romance of the Rails that cost overruns on 64 main urban rail

projects financed by the federal government averaged 43 percent.

5. Aid is contingent on expensive regulations. Since the first aid program

for land-grant colleges was established in 1862, state and local agencies

administering the programs have been subject to regulations imposed by the

federal government. As of today, aid recipients are burdened with mountains

of environmental, labor, and safety regulations imposed by the federal

government. As a result of these regulations, project costs increase. As an

illustration, Davis-Bacon regulations mandate that laborers engaged in

federally funded construction endeavors are generally entitled to higher

union wages; this stipulation results in an approximate 20 percent

escalation in project wage expenses. Aid-related federal environmental

regulations also cause project delays. Since the 1970s, the average time

required to obtain federal environmental approvals for infrastructure

projects has increased from 2.2 to 6.6 years.

6. Aid stifles diversity in policy. Different states may have distinct

policy preferences regarding, among other things, education, transportation,

highways, and taxes. State and local governments can maximize value in the

federal system of the United States by basing their policies on the

preferences of their constituents, while individuals can enhance their

quality of life by relocating to jurisdictions that are more to their

liking.

Federal aid and associated regulations undermine the diversity of beneficial

state policies and local options. An illustrative instance was the

nationwide speed limit of 55 miles per hour, which was implemented from 1974

to 1995 under the threat of federal highway aid withdrawal. These

one-size-fits-all regulations are detrimental to value because they

disregard variations in state geography, traditions, and resident values.

"The nature of our constitutional system encourages a healthy diversity in

the public policies adopted by the people of several states in accordance

with their own conditions, needs, and desires," stated Executive Order 12612

on federalism issued by President Ronald Reagan in 1987. "States and

communities are free to experiment with a variety of approaches to public

issues in pursuit of enlightened public policy." However, states cannot be

free to experiment if Washington dictates public policy through aid

programs.

Although Reagan identified as a conservative, liberals have also advocated

for policy diversity as a social ideal. In 1932, liberal Supreme Court

Justice Louis Brandeis stated that federalism allows each state to "act as a

laboratory and try novel social and economic experiments without endangering

the rest of the country." Pursuing policy experiments at the state level

entails a lower degree of risk compared to their federal counterparts, where

the nation suffers when federal politicians commit catastrophic errors. The

mid-20th century high-rise public housing initiatives serve as an

illustrative instance, currently recognized as a policy catastrophe. Why did

numerous American cities erect unsightly concrete fortifications for the

impoverished and bulldoze neighborhoods? Because the initiatives were funded

and promoted by the federal government,.

7. Aid undermines democracy. Policy decisions regarding federal aid programs

are frequently rendered by unelected officials based in Washington, DC, as

opposed to elected officials at the local level. Aid programs delegate

decision-making authority from the over 500,000 elected state and local

officials in the United States to thousands of unidentified and inaccessible

federal agency personnel.

While the 535 elected members of Congress are ostensibly responsible for

overseeing assistance programs, the majority of their authority has been

delegated to federal bureaucracies. You may express your disapproval of a

policy implemented by your child's public school to local officials.

However, if Washington imposes the policy, it will be difficult for you to

have your concerns addressed.

Moreover, the enormous scale of the federal government hinders democratic

participation. Given that the federal budget is one hundred times larger

than the average state budget, state and local policymakers have more time

than federal policymakers to address citizen concerns regarding a program.

Former U.S. representative: "Citizens are effectively disenfranchised" due

to the federal aid system. According to Saving Congress from Itself:

Emancipating the States and Empowering Their People, a 2014 book by Senator

James L. Buckley,.

Each state is guaranteed a representative democracy, or a "republican form

of government," under the U.S. Constitution. However, this guarantee is

weakened whenever the states become bureaucratic subdivisions of the federal

government. Federal aid comprises 25% of the expenditures allocated to state

and local governments. This 25% portion serves as the foundation for program

control at the federal level, owing to the regulatory authority vested in

the federal government.

Without a Child Left Behind program: a collection of top-down mandates

imposed on public schools by the George W. Bush administration. The

administration of Barack Obama attempted to micromanage neighborhoods by

regulating federal housing funds. The administration of Donald Trump

threatened to reduce funding to public schools that failed to adopt its

reopening strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic. It would have been more

prudent in each of these situations to repeal the aid programs that formed

the foundation and permit the states to fund and manage their own

initiatives.

8. Assistance erodes accountability. In its inception, the three tiers of

American governanceófederal, state, and localóresembled a well-organized

layer cake, wherein distinct responsibilities were assigned to each tier.

The public was aware of who merited commendation and who merited censure for

policy actions. However, as aid has increased, the government has evolved

into a marble cake, with policy responsibilities distributed across multiple

strata. Reagan lamented in his budget message to Congress in February 1982,

"Over the last two decades, the once-clear delineation of responsibilities

and obligations among the federal government, states, and local governments

has transformed into a disorganized and perplexing jumble."

The disarray has impeded the ability of the public to hold politicians

responsible. Politicians tend to attribute responsibility for failures to

subordinate branches of government. They place the responsibility for

inadequate calamity responses, substandard public school performance, and

numerous other disappointments on others. When each government participates

in an endeavor, failings are not the responsibility of any government.

9. Assistance disrupts private activities. Federal assistance motivates

state governments to eliminate or "crowd out" private service providers.

Infrastructure investments in airports, transit systems, and bridges

illustrate this issue.

Due to the expansion of federal aid, private highway bridges were crowded

out. Robert Poole noted in Rethinking America's Highways: A 21st-Century

Vision for Better Infrastructure that the majority of toll bridges in

America were formerly privately owned. However, beginning in the 1930s,

federal and state governments subsidized government-owned bridges, putting

private bridges at a competitive disadvantage and resulting in the

government's acquisition of many of them.

Prior to the 1960s, urban transit systems in the majority of American cities

were privately owned and operated. Subsequently, private transit began to

decline. The rise of automobiles undermined private transit, but the Urban

Mass Transportation Act of 1964, which offered federal assistance to

government-owned bus and rail systems and encouraged governments to take

over the private systems, put an end to that.

An analogous event transpired within the realm of aviation. During the early

years of commercial aviation in the 1920s and 1930s, approximately half of

U.S. airports were privately owned, including the primary airports in Los

Angeles, Miami, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. Although the airports

were prosperous and pioneering, they succumbed to unjust government

competition. Government airports were exempt from paying taxes and could

issue tax-exempt bonds. Then, in 1946, the federal government initiated a

policy of consistent aid payments to airports owned by the government. This

ultimately resulted in the demise of private commercial airports.

In summary, the federal aid system finances state and local activities in an

indirect and ineffective manner. Aid administration results in wasteful

expenditure and bureaucracy. It undermines democratic control and policy

diversity. It represents a triumph of irresponsible spending and should be

reduced and eventually eliminated.

|